LA MÚSICA

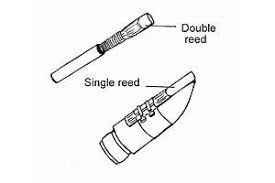

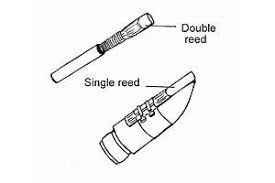

Did you know that the oboe is a double reed instrument, requiring the player to blow air through two pieces of cane tied together that then vibrate against each other? Do you know what the word embouchure means? Were you aware that after spending two years learning how to play a double reed instrument in America, a novice oboist must adapt to a European double reed when in Spain, all the while taking two buses across town, past the Río Genil, into a neighborhood marked by streets named after noted Spanish journalists, artists and musicians?

Double the pleasure! Double the fun!

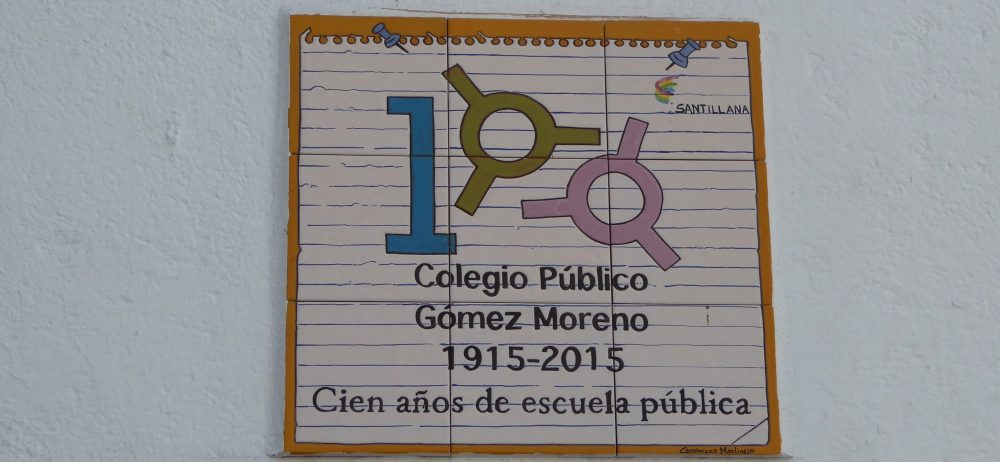

All this to say that once a week, A., along with one of her moms, travelled forty-five minutes to meet with Paloma Θ in an apartment located on Calle Pianista Pepita Bustamante ⊕ to continue her oboe studies, now with a European reed ⊗.

Has already walked to center of town, taken the LAC and gotten off at the Mercadona, crossed the Río Genil and is now boarding the S1.

Heading down the aforementioned calle.

Standing in front of the previously referenced apartment block.

Entering the place of study.

A. + Paloma = !!!

Θ Paloma: Exceptional oboist who plays in orchestras in Málaga and throughout Germany. Uses European reed.

⊕ Pepita Bustamante: Played piano; used neither European nor American reed.

⊗ European reed: “American scrape reeds are scraped further down towards the thread than European reeds. Also, gouge/shaper width is different (European reeds tend to be wider) . . .

“Other than the garble of these technical differences, the main difference is the way they function. The idea behind the American reed is to allow the player to play minimal strain/embouchure manipulation while maintaining pitch and tone quality. European reeds, on the other hand, require more embouchure/muscle manipulation/strain. They also sound different (compare John Ferillo, John Mack, Liang Wang, etc. to Albrecht Mayer, Francoix Leleux, etc.), which could make one style appeal over the other. “

https://www.reddit.com/r/oboe/comments/7yotck/american_vs_european_scrape_reeds/

Oh, happy days! Often, A. and one of her moms, would walk back to the Albayzin as dusk turned to dark. Down Avenida de Cervantes, skirting the park along Paseo de los Basillos and up into the Realejo they walked, passing cafés, papelerías, bars, fruit stands, chocolate shops, art stores — everything open and people out and about after the long mid-day siesta. In winter, they bought paper cones of chestnuts freshly roasted on an open brasier and in spring they settled for any number of dry and often tasteless Spanish pastries.

LOS ANIMALES

You can help!

With a “Can Do!” attitude, three young Americans arranged a fundraising activity to support one of the local refugio de animales located on the outskirts of Granada. As mentioned in a previous post, the Albayzin is home to a large and fascinatingly varied assortment of dog poop. This poop is accompanied by a large and varied assortment of bedraggled and sad-seeming mutts. These mutts evoke various feelings depending on how cute they are, if running sores are open or closed, and if any of them have pooped near your doorstep.

The idea was to offer baked goods for sale at the mirador at San Miguel Alto, a prime sunset spot for both locals and tourists. Having people pay for a piece of cake, of which the proceeds would go to some organization, was an odd practice in Spain, where the government actually provides enough money for an array of social services.

La preparacíon.

Cositas dulces.

Waiting for customers at Hermitage de San Miguel Alto.

Customers arrive!

A discerning shopper.

What people actually came to look at…

…as the springtime sun descended.

Neither horse nor rider deemed to make a purchase.

In the end, these do-gooders made over 170 euros!

Full moon over snow-covered Sierra Nevada from mirador San Miguel Alto. Sigh.

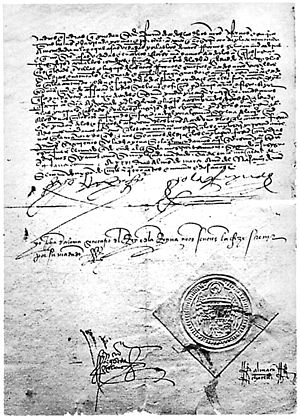

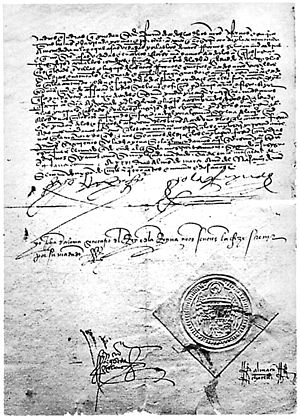

LOS JUDÍOS

With the passage of the Alhambra Decree of 31 March 1492, the Jewish population of Spain was, for all intents and purposes, eliminated. King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, honorifically titled Reyes Católicos, gave the Jews four months either to leave Spain, to convert to Catholicism, or to be executed. This explains the powerful effect our family had upon the observant Jewish community of Granada in 2015, essentially doubling its numbers by our mere arrival.

The Alhambra Decree, also known as the Edict of Expulsion. Decreto de Alhambra, también conocido como el Edicto de Expulsión.

Along with two of our ex-pat friends and the arrival of Tia S., the Jewish population, as far as we knew, burgeoned to twelve. Six or seven joined together in ritual, repast, and red wine as the cycle of holidays turned round.

Home made latkes con las judías.

Hannukah with home made hannukiah and dreidel.

The festival of lights.

Singing and dancing.

A Passover seder.

Automatic timer works.

“Granada’s only Jewish museum” (Trip Advisor), the aptly named Palacio de los Olvidados” — the Palace of the Forgotten — was a collection of items not to be missed. The museum and cultural center is located in the Albayzin and funded by a Spanish gentile of some means who has collected artifacts of Jewish life that span the centuries. We visited this quiet place at the beginning of our stay. {For actual, worthwhile information about this attraction, please go to http://www.palaciodelosolvidados.es/.}

The Realejo, regarded as a vibrant and semi-hip area abutting the Alhambra, is marked on its west side by a statue of Yehuda Ibn Tibbon, noted Jewish translator and physician of 12th century Andalus. (We mention this only to provide context for the photograph that follows.) In this neighborhood we happened across a sandwich board chained to a lamppost (photograph accidentally deleted) advertising Centro de la Memoria Sefardí. This small museum is housed in the home of a French woman, Beatriz Chevalier-Sola. Beatriz had returned to Granada sometime after the year 2013 when the Spanish government began offering citizenship to any Sefardi Jew who could prove Iberian ancestry. This kind woman invited us to return to her home to celebrate Rosh HaShana, hence our introduction to the five other observant Jewish people now living in Granada.

Bathsheva Chevalier-Sola and Joseph ben Abraham Camerero.

Though a far cry from the estimated 50,000 Jews who lived in Granada at the end of the 15th century, the ten of us who gathered round as Beatriz’s husband Joseph ben Abraham Camerero read from the Five Books of Moses recalled a past that the reader must ponder in silence.

-

-

Granada’s original judería.

-

-

Yehuda Ibn Tibbon. His foot is shiny because it is easy to reach.

-

-

Entrance to Museo de la Memoria Sefardí.

{Addendum: By the time we left Granada, the Palacio de los Olvidados had rebranded itself as a museum of the Inquisition and torture. Attendance is up!}

EL SENDERISMO

Surrounded as we were by mountain chains such as the Sierra Nevada, the Alpujarras, Sierra de Huétor, Sierras de Alhama and Tijeda Y Almijara, it did not take long for A. and J. to appreciate a brisk hike, mountain air and lovely vistas.

We reach our destination.

The view is breathtaking.

The mood lifts!

It is always better on the way back.

Hiking became second nature, as simply getting from one place to another in the Albayzin required a vigorous up and down over winding and cobbled streets. Outings were as fun as they were effortless, whether it was walking 2.1 kilometers to El Corte Inglés in search of maple syrup (63 meter elevation loss and gain), or 1.8 kilometers to the Generalife to inhabit a paradisal garden (87 meter loss and gain) or even 5.0 kilometers to the outlying district of El Fargue (272 meter loss and gain) for a menu diario at the Terraza El Caldero.

We walked to Café Quatro Gatos, but it was closed in August when we arrived.

We walked to the center of town, the intersection of Calle Reyes Católicos and Gran Vía de Colón.

We walked up to the sports complex at Aynadamar.

We walked here, across from the Sierra Nevada.

We walked at night in the Albayzin.

We walked along al-Sabika, high above the Río Darro.

We walked past the old city walls to San Miguel Alto.

We walked to the mini-market Hay de Todo.

We arrived there.

We walked past plates.

We walked to the Río Genil….

… and met this silent, gilded woman.

We walked to Bar Aixa.

We walked up the steps to the mirador.

And we walked with our friends to the local mezquita.

We walked past flowers.

We walked until we got there.