Winter break arrived. We went to Italy. We stayed for three weeks. Like many tourists, we saw lots of sites we had previously read about in books and magazines or seen in movies and documentaries. Usually when reading books that take place in Italy or watching movies that feature Italy, you are content and comfortable, happy to be doing what you are doing. The people around you leave you alone, knowing that you are occupied in your enjoyment. They don’t pester you to stop reading or ask you to leave the movie before it has ended so they can go home and play a computer game. We bring this up only to provide context for the following account.

I. Arriving in Venice. We take the water taxi from the airport to Fondamenta Nuevo.

I am where I want to be.

The high speed taxi took us exactly where we wanted to go.

A. and J. are happy to be where they are.

The sun in its proper place.

Fondamenta Nuevo is where we want to go.

II. Exploring Venice, the City of Bridges. We make our way on foot and float.

In Venice, we spent our days walking from one islet to another searching for gelato, seeking out espresso, and listening to an endless argument in favor of returning to the apartment to do something that was actually interesting.

From islet to islet ….

On the Ponte dell’Accademia.

Searching for a fire….

A church that seemed photogenic at the time.

Riding the vaporetto.

Police at the ready.

I am doing what I want to be doing.

Riding the Stone Lion.

A stranger has taken our picture at Piazza San Marco.

Something actually interesting.

III. Visiting the islands of Murano and Burano. We embrace winter in Northern Italy.

One day we traveled via the local water bus to the islands of Murano and Burano, a scenic ride we’d been told. On Venice, docks line the Grand Canal and the Fondamenta Nuevo. You simply buy your ticket, find the proper loading dock, wait for your boat and hop on board. Murano is a glass buyer’s Eden. Long-standing factories guard their secret glass-making processes carefully. Along the central canal on Murano, specialty shops provide the glass-crazed tourist an array of rare keepsakes. Once entered, each store offers opportunities to unintentionally break expensive pieces of handblown art. On the island of Burano, conversely, the blood pressure lowers. Here the visitor can purchase handmade lace (non-breakable), enjoy the fanciful painted houses (impossible to drop accidentally) or watch an old man clean the guts out of a fish, pier-side. (Photo unavailable due to expired camera battery.)

We sail to the island of Murano.

Glass is blown there.

We are not allowed to tell you how the master completes his craft.

By remaining outside the store, it is impossible to break the objects inside.

The one piece of glass that you can not purchase in Murano.

Cheerful Burano houses.

Breaking and entering.

On Burano, feral cats abound.

Winter in Venice.

IV. Soaking up local culture. We try to keep everyone happy.

As you are likely aware, when traveling with more than two people the number of decisions to be made increases exponentially. We used a system of barter, trade, promise and bribe to make the process work smoothly. As a result, we were all able to ride on a gondola, visit the Jewish Ghetto, and spend time at the outdoor Rialto Market where we watched attractive young men lure squat middle aged housewives into buying miracle mops. In addition, during the course of our stay in Venice, select members of our party consumed 14 cans of Fanta Orange Soda, 10 ice cream cones, 6 cups of hot chocolate, 2 bags of specialty candy and 3 bottles of wine.

We stopped by twice but he was never home.

In this moment, A., J., M. & D. experienced happiness.

Our gondolier had to wait 10 years to earn his spot. Now, he is happy.

From the point of view of a gondola.

Rush hour.

Winged Lion + Open Book = Peace.

At the Rialto Market, A.& J. wanted to try these.

We explore Europe’s first Ghetto! (Jewish)

Inhabitants had to build up, as they were not allowed to live outside their neighborhood.

Book still open…..

Everything moves by boat.

Our local Campo.

“You lookin’ at me?”

Award winning monument takes First Place in Premio d’Italia.

Lessons learned: There’s a lot to say about Venice: the origin of the word ghetto, the reason each islet has its own church, why everything costs twice as much as in Spain. All these things we discovered. But as is the case in much of Italy, everything that you learn in one city, you quickly forget in the other.

We remember the Grand Canal.

We remember to bring J.

We remember our train tickets.

We remember to keep our eyes open.

V. Confronting the artistic treasures of Florence. We consider the human form, in all its natural beauty.

As soon as you leave the central railway station, Firenze Santa Maria Novella, you find yourself in a city defined by its Renaissance architecture, its flagstone streets, its cathedrals, palazzios, wide slow river and a number of large naked men cast in bronze and chiseled in marble who stare blindly ahead, ignoring your wide-mouth stares.

Why is everybody staring at my corpus?

They are staring at my corpus, fool, not yours!

Is it true that I have a bird on my head? And if so, is anyone looking at it?

I have a crown, but alas, no bird…

At least I’m dressed.

We arrived in Florence on Christmas Eve day. The city was alive with visitors, all (except one) eager to sample the visual delights of what was once a Medici stronghold. Happily we scampered across the Ponte Vecchio, through the neighborhood of Oltrarno and up the hill to Piazzale Michelangelo to marvel at vistas from south of the Arno River. Here we could spot Palazzo Vecchio, the Duomo, Giotto’s bell tower, and the copper-domed Great Synagogue — all places that would be indelibly impressed upon the under-11 set in the ensuing days/daze.

Ponte Vecchio with red and white pennant.

Famous sites from afar and at a slight angle.

Proof that we were there.

Tempio Maggiore

Actually, I ordered the tagliatelle.

VI. Desperately recalculating. We select child-friendly activities.

The thing is, there is a lot of fun stuff to do in Florence if you put aside the treasures of the Uffizi, the treasures of the Pitti Palace, the Leonardo da Vinci Museum — with its special treasures — the Bargello Museum [treasures galore], the Opera del Duomo, complete with its own amazing treasures, like Ghiberti’s sculptural bronze doors, etc., etc., etc. Though a certain credit card company has informed us that the best things in life are priceless — hence leading any reasonable person to assume that it wouldn’t hurt anyone {even if he is 7} to look briefly at Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise or Botticelli’s Rite of Spring — for just a handful of euros you can have a pretty good time renting bikes or for no money at all taking pictures of inanimate objects.

Priceless.

Donations accepted.

No charge, except for Yoga class.

Reasonably priced child-friendly activity.

Down jacket was a freebie.

87,000 Euros (adjusted for inflation).

VII. Asserting parental control. We become one with the artistic culture that surrounds us.

Even J. thought it was special.

We waited in line to climb up Giotto’s Bell Tower…

But not as long as these folks had to wait.

Brunelleschi contemplates his masterpiece.

His masterpiece (Il Duomo).

Heaven and hell in-the-round.

The artist Jeff Koons is allowed to do this. We still do not know why.

By the fourth day in Florence we were beat looking at all that art and architecture. We decided to take the train to Pisa to see if we could make the Tower fall down.

Everything in Pisa seemed a little off center.

They named the river walkway after this gentleman.

Same fiume as in Florence.

The outside of a famous tower in Pisa.

The inside of the very same tower.

This puppy really leans!

But which way?!!!

Ah…that’s better.

J. does his part to keep the tower upright, regardless of our initial plan to push it down.

The setting is quite lovely.

The train back to Florence rocked, but did not lean.

Pisa offered simple pleasures after all the cathedrals, palaces, galleries, churches, museums, facades, pediments, and selfie-stick sellers of Florence. When you climb the Leaning Tower of Pisa, the gravitational force flings you from one side of the stairwell to the other. Also, if you appropriately time your visit to Italy’s largest baptistry, which is the Pisa Baptistry of St. John (0.6 degree tilt), you can hear a guard call out musical notes and experience an acoustically perfect resonating chamber.

Lessons Learned: There’s much to say about traveling in Italy for three entire weeks with children. And apparently a lot of parents have already said it on blogs of their own, which we never bothered to read until it was too late.

Happy to be by the Arno River.

Improves reception in 4 out of 5 Florentine homes.

Happy to be in the Boboli Gardens.

VIII. Seeking the ruins of a lost civilization. We try to discern meaning from 170 acres of ruble.

First things first — the best gelato on the entire Italian peninsula can be found on modern Pompei’s main square. Here’s a big shout-out to Emilia Cremeria, Piazza Bartolo Longo, 54! Now, on to other business….

In 3rd grade, A. completed a research project on Pompeii, a once-thriving middle class city situated on the Bay of Naples that was destroyed, and yet preserved, in AD 79. We now had a chance to visit this historic site and see how things stacked up in relation to A.’s own work on the subject.

-

-

Amphitheater still standing? Check!

-

-

Sidewalks still passable? Check!

-

-

Bodies still baked to a crispy crunch in perpetuity? Check!

Our guide to the ruins of Pompei, Alex, spent a few hours explaining this and illustrating that, and it was a good thing he did, because with out his help we would have ended up just another set of tourists looking in vain for a long-lost trattoria or VIP brothel.

Local fast food joint from 2 millenia ago.

Alex explaining something fascinating of which we have no memory what so ever.

Walking the streets of Pompei, hoping we do not stumble upon the Lupanare Grande, the most famous brothel of Pompei (according to Wikipedia).

After we said our good-byes to Alex, we were determined to make our way on our own to the famous House of the Faun, so named due to the mythological creature, half-man, half-goat, in this case cast in bronze, situated in the middle of the House’s impluvium (no offense).

-

-

I am only a facsimile; the actual me is located in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale.

{NOTE: When seeking the House of the Faun, be sure to turn left at the corner of REGIO III, Insulae 7, 23 and REGIO IV, Insulae 14, 21 or else you will end up at the intersection of REGIO VII, Insulae 13, 5 and REGIO VIII, Insulae 10, 6, otherwise known as the Lupanare Grande.}

Pompei certainly deserves more than the four hours we allotted it, but due to the combustibles we were carrying with us, our time was limited before they exploded full force.

-

-

Adult shoes and combustible shoes on top of ancient tile.

-

-

Combustibles contained.

-

-

The ancient city of Pompei safely free of combustibles.

When you visit, do not miss strolling around contemporary Pompeii. Lots of adventures await the curious traveler. For instance, M. lost a stare down with a nun at the Pontificio Santuario della Beata Vergine del Santo Rosario di Pompei (otherwise known as the Cathedral) and ended up having to pay double for the family to ride the elevator to the top of the bell tower. Result: we reluctantly contributed eight extra euros to the sustenance of the Church, and more importantly, vowed never to attend Mass again.

Lessons learned: a.) Pompeii can be spelled with either one “i” or two and we had neither the time nor the inclination to be consistent in this post. b.) Order the house red; it is always delicious and always a good price. c.) The kids are all right.

-

-

When you stay at the Hotel Diana, your room comes with its very own portable Diana!

-

-

Modern Pompei – a nice place to visit.

-

-

J. takes the only decent photograph on the blog.

IX. Preparing to tour Rome. We avoid all cliches.

Rome was not built in a day, even though all roads lead to it. This was the koan we pondered as we walked the black-cobbled streets of the Centro Historico. By now, sixteen days into our journey, we had abandoned our copies of Henry James’s The Ambassadors and E. M. Forster’s A Room With a View. Sitting quietly, reading, absorbing the essence of Italy through the eyes of foreign writers whose works had been converted into simple-to-digest movies — this was not for us.

Romulus, Remus & the famous She-Wolf.

We visit the Pantheon with our fellow travelers.

The oculus allows light and rain to enter the Pantheon.

One of the worthwhile items we read in Italy.

Passing down café lore at Caffé Sant’Eustachio.

We arrived in Rome on New Year’s Eve day. Signs of Christmas and Three Kings’ Day were apparent in the bakeries and candy stores in our wanderings. We were surprised to learn that Roman families actually put coal in their children’s Christmas stockings!

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Our apartment, loaded with guidebooks, but not a single copy of Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, was located right off Campo de’ Fiori in the Centro Historico neighborhood. We spent most of our time reading these contemporary tomes, discovering in words and pictures, the bountiful offerings of Rome that we might never cajole A. and J. to visit in real life.

As was customary, we visited Il Ghetto, what was once the Roman Jewish Quarter, a former lowland swampy place abutting the River Tiber that flooded regularly and was home to pestilence, ill-health and a thorny thistle we call the artichoke. From this came the now-famous and delectable Carciofi Alla Giudia — Artichokes Jewish Style — deep-fried, crispy and containing absolutely no jamon.

100% kosher.

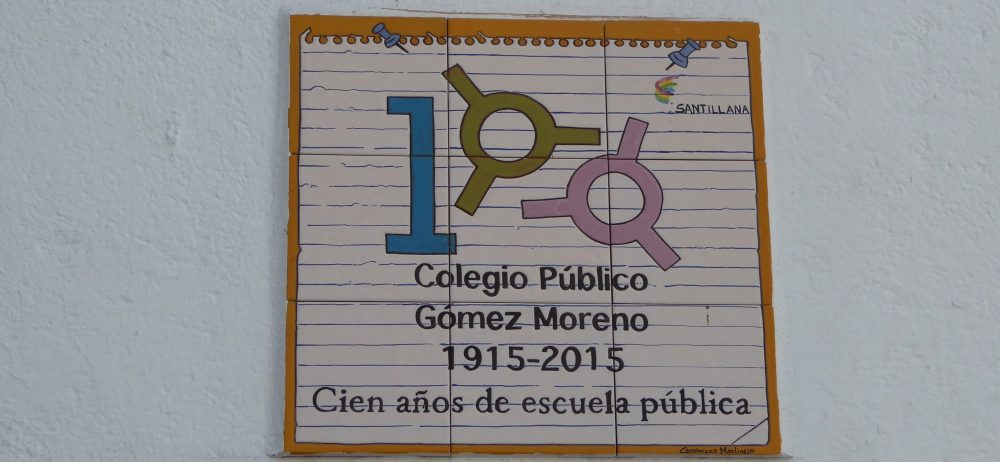

Artichokes prepared in such fashion, a few bakeries, a fountain designed by Bernini in honor of the Jews, some wall plaques and an enormous synagogue (built 1901-1904 C.E.) mark the history of the ghetto, whose walls were torn down in 1870 when the Papal State ceased to exist. (See: Viva d’Italia, directed by Roberto Rossellini, 1961 C.E., starring Renzo Ricci, Paolo Stoppa, and Tina Louise.)

Bernini likened the Jews to the turtle, for their equal ability to travel at a moment’s notice with everything they needed on their backs.

Reminders of days of yore.

Makes a bold statement, after years of oppression.

Jewish kids had to go to school here.

X. Crossing the Tiber. We journey to St. Peter’s.

According to every guide book we consulted, no visit to Rome could be complete without crossing the River Tiber and making one’s way to Vatican City. When confronted with a chance to admire Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, climb the Basilica of St. Peter’s, and gape at the incalculable aggregation of material wealth within its sanctuary, it was a no-brainer.

As many people know, St. Peter’s Basilica is located in Vatican City State, a sovereign entity complete with its own postal system, security personnel, telephone service and pharmacy, though no carry out pizza.

First cross this river.

Next, follow these signs.

When you get there, climb to the top of St. Peter’s Dome.

Then scurry down to hang out in the ellipse and expectantly wait for nightfall.

The Trevi Fountain, the Spanish Steps, the Forum, the Colosseum….a blog post like this could go on for days. And even though those sites were a wonder to behold, as we snuggled up next to our other tourist friends, in truth, the little moments had as equally great impact upon us as well: watching a man in Piazza Navona make art out of a can of spray paint and a piece of cardboard and still remain conscious; stumbling across a tiny store in Il Ghetto that sold pepper sauce in sixteen different strengths and surviving the hottest on a dare; and finally, getting the chance to stay inside and play Minecraft on a laptop while the Eternal City thrummed vibrantly right outside the door.

The Trevi Fountain: a popular destination.

The steps were being renovated. All we could see was this sign.

The Roman Forum (according to our guidebook).

A large monument in honor of the Romans’ defeat of Judea.

The spoils of war.

Built in 2,920 days.

Pretty cool, even if you haven’t seen Gladiator.

Another large monument, this time built in honor of Victor Emmanuel II, of whom you have probably never heard.

Only monument in Rome not made out of stone: the Italian Stone Pine. (No joke.)

Lessons Learned: Rome is a fantastic city to visit, with or without children. The people are friendly, the food is delicious, and you can walk everywhere you want to go. Don’t forget to bring the chargers and the adapters!

Still speaking to each other on Day 20 (Colosseum, Rome).